Learn about crypto & Trading

Explore articles and resources to master cryptocurrency trading

Basics of Crypto

What is a Blockchain?

Definition

A blockchain is a highly-secure distributed database. The computers forming a blockchain network – called nodes – all hold the same information history. As such, the database is decentralized and users do not need to trust an intermediary to validate the information they receive. As intermediaries are redundant in most cases, individuals can exchange information on a peer-to-peer (P2P) basis. Each new information sequence forms a block which is chronologically chained to the database. This forms a chain of blocks or blockchain.

Main Characteristics of a Blockchain

Those analyzing blockchain data should pay attention to underlying technology related to the information they are interested in. There can be significant differences in the way blockchain protocols are structured.

A blockchain can be public – for instance, anyone can view the record of Bitcoin transactions – or private – such as an internal company database running proprietary nodes. For private or permissioned blockchain protocols, the term distributed ledger technology (DLT) is preferred. Most cryptoassets are built on blockchains, but this technology has other use cases. Indeed, a blockchain can record data relating to real estate ownership, intellectual property and fiat currency. In this sense, it can facilitate the transfer of these assets.

To make additions to the blockchain, each node must agree that the participant has the ability to do so. To that end, blockchains are secured by cryptography to approve any changes. Cryptography is an encoding method which ensures that users have the right to add or view data by solving a cryptographic puzzle. This is called the blockchain’s hash function. The process of approving changes to the blockchain is known as mining. The node which solves the cryptographic problem first receives a block reward – a given quantity of a cryptoasset, for instance.

Users often hold a public and private key pair. The public key is similar to an email address as it is known to the entire network and can be used to send or receive information. The private key is comparable to a password which allows access to personal information and adds information to the blockchain. Many cryptoasset businesses manage public and private keys on behalf of their customers, much like traditional banks. A user’s collection of public keys – cryptoasset addresses – is referred to as a cryptoasset wallet.

Compliance & Blockchain Analytics

Compliance teams in the cryptoasset industry can leverage the immutability characteristic of blockchains. Indeed, transactions on public blockchains (e.g. Bitcoin) can be audited by anyone. Anyone can use a blockchain explorer such as Blockstream.info to browse activity on a single blockchain. Chain Monitoring Group leverages its research capabilities to label the actors transacting on cryptoasset blockchains to detect and prevent illicit activity. As existing blockchain data cannot be modified or deleted, criminals can be tracked long after the illicit activity occurred.

What is a Cryptoasset?

Definition

Cryptoassets refer to digital assets that are secured by cryptography. These include digital currencies such as Bitcoin, digital representations of physical assets such as wine, and non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which represent a unique digital asset. Cryptoassets are different from fiat currencies which are issued by governments or central banks. They can be transferred digitally without the need of a financial intermediary.

Main Characteristics of a Cryptoassets

Most cryptoassets are built on blockchain networks which share some of these characteristics to varying extents:

- Decentralized governance: no central authority.

- Open (permissionless): protocol is available to anyone and anyone can interact with the network.

- Borderless: not restricted to a jurisdiction.

Cryptoassets and Financial Crime

Compliance professionals will be aware that cryptoassets have been linked to illicit activity. However, Chain Monitoring Group estimates that less than 1% of cryptoasset transactions were linked to illicit activities in 2021. Comparable to fiat transactions, financial crime risks in cryptoassets can be controlled with effective risk assessments and compliance programmes. As detailed below, most cryptoasset transactions are not anonymous contrary to popular belief.

Cryptoassets and Pseudonymity

Most cryptoasset addresses are linked to a wealth of information such as transaction history, which is publicly available on the underlying blockchain. In turn, most addresses are controlled by an individual or an entity. When actors intentionally or unintentionally reveal they are connected to a particular address – for instance, by posting their cryptoasset address on social media – it can be reconnected to an identity. All the transaction data and funds held in that address are no longer pseudonymous.

Privacy Coins

A few cryptoasset projects have emerged with the goal of enhancing the user’s privacy. Popular examples of cryptoasset with privacy enhancing features include Zcash and Monero. Their protocol allows users to shield transactions and cryptoasset holdings on the public blockchain unless they present a given cryptographic key. While this poses a challenge for compliance professionals and law enforcement agencies, this does not mean that a transaction history does not exist. Unlike cash, in most cases such data is available for users which hold audit or private keys. These can become very useful in the context of an investigation.

Chain Monitoring Group supports a number of privacy coins such as Zcash and Horizen. This enables compliance teams to lower their risk when dealing with these assets or when exposed to actors handling such assets.

What is DeFi?

Introduction

Decentralized finance (DeFi) mimics many traditional financial services, but with a key change – there is no reliance on a central intermediary. Instead, the services are created using smart contracts (self executing code) built on permissionless blockchains such as Ethereum.

This allows anyone with the required computer engineering skills to create a DeFi service, and anyone with access to an internet connection and cryptoasset wallet to access it.

In November 2021, more than $247 billion was locked in DeFi services, and although total locked in value (TLV) has been turbulent through 2022 with high-profile DeFi service insolvencies, the amount users have within DeFi applications is still worth tens of billions of dollars.

However, this large pot of money also acts like a honey pot to illicit actors and as of November 2021, it is estimated that DeFi users have lost more than $12 billion due to theft and fraud. Elliptic refers to this as decrime and we cover this in depth within our 2022 report: DeFi: Risk, Regulation and the Rise of DeCrime.

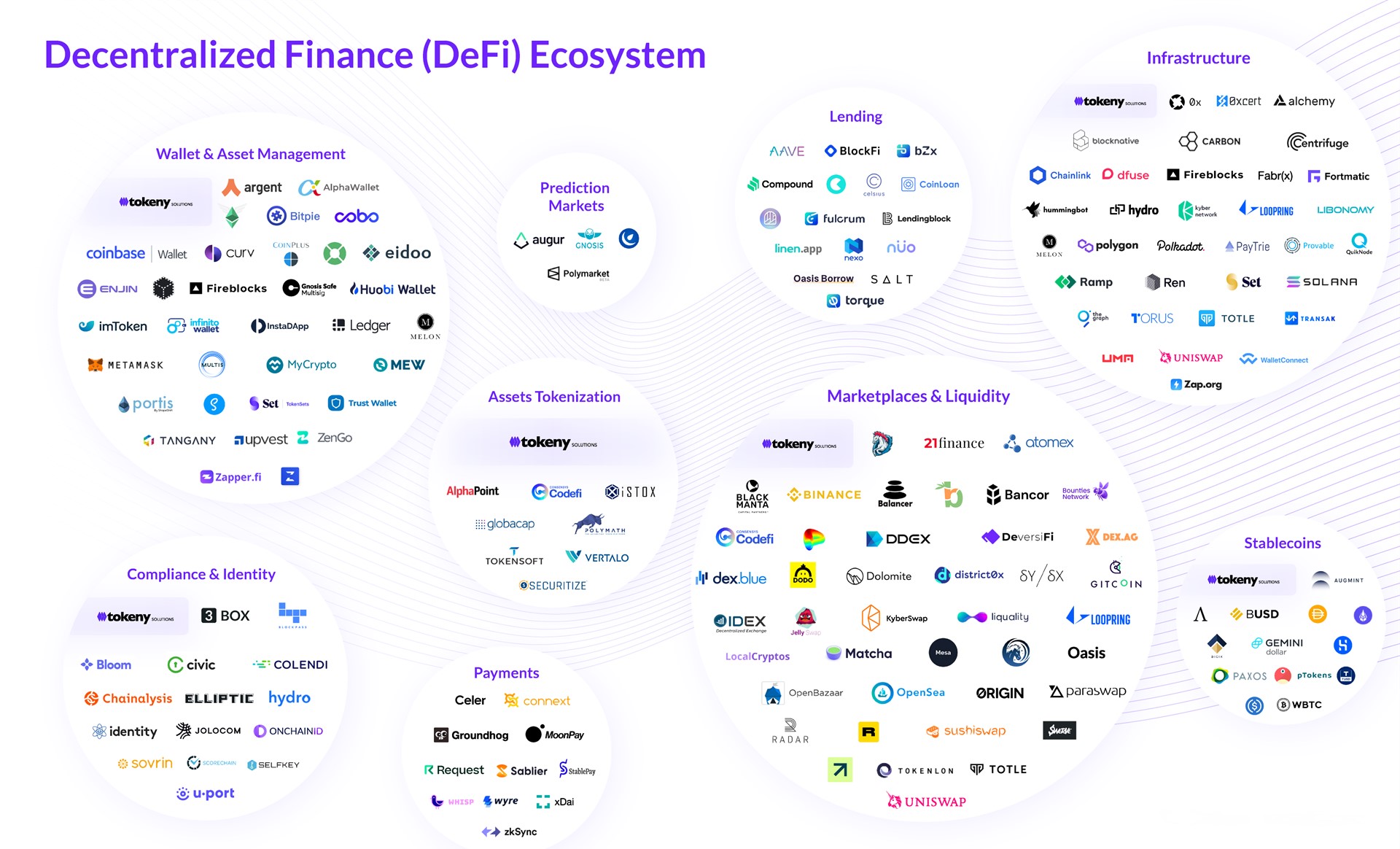

The DeFi Industry

As noted above, the DeFi industry seeks to provide financial services without the need for a trusted intermediary. Some examples of DeFi services are:

- Lending and borrowing: being able to earn a yield by offering out your cryptoassets so that others can utilize them.

- Wallet and asset management: services which help you to manage and secure your crypto wealth.

- Stablecoins: cryptoassets which seek to maintain a peg with a fiat or other digital assets.

- Decentralized exchanges: marketplaces which allow users to exchange cryptoassets without needing to place funds into centralised control or custody.

- Complex financial products: mirroring the traditional finance (TradFi) investment banking sector, users can trade perpetuals, synthetics and options based on cryptoassets.

The DeFi industry is a growing sector with many new use cases and projects spinning up. So, we will continue to see new innovations and applications.

DeFi Risks

Due to DeFi applications being a complex web of smart contracts, there have been many hacks which take advantage of unaudited infrastructure, unintended bugs in the software, and weak cybersecurity standards.

Chain Monitoring Group estimates that 90% of lost funds in DeFi are linked to bug exploits, which can be of two types. The first is a code exploit due to a coding error in the smart contract’s code. The second is an economic exploit often due to smart protocols unintentionally allowing price manipulation and creating arbitrage opportunities.

DeFi protocols are also likely used to conduct money laundering activities. This is due to the fact that the vast majority require no know-your-customer checks and simply require the user to connect with their cryptoasset wallet to get started. You can read more about the risks of crime in DeFi in our 2022 report: DeFi: Risk, Regulation and the Rise of DeCrime.

DeFi & Compliance

There is a growing view that developers of DeFi projects may be held accountable to conduct anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) checks as regulated entities – or be mandated to include it in their software by design – in certain instances. For example, if a group of developers with a majority stake in a project operate and market it as a business, then it is likely to fall under the regulator’s scope.

For example, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) argued that the smart contracts running on blockchains underpinning DeFi are not as decentralized as they purport to be. The authors claim that there is some level of centralization which revolves around those who write the protocol and set strategic priorities. These actors, they note, “are the natural entry points for policymakers” seeking to regulate the DeFi space.

In its October 2021 updated guidance on cryptoassets, the FATF also seemed to contest the decentralized nature of DeFi. It wrote:

“A DeFi application – i.e. the software program – is not a VASP under the FATF standards, as the Standards do not apply to underlying software or technology […]. However, creators, owners and operators or some other persons who maintain control or sufficient influence in the DeFi arrangements, even if those arrangements seem decentralized, may fall under the FATF definition of a VASP where they are providing or actively facilitating VASP services.

“This is the case, even if other parties play a role in the service or portions of the process are automated. Owners/operators can often be distinguished by their relationship to the activities being undertaken. For example, there may be control or sufficient influence over assets or over aspects of the service’s protocol, and the existence of an ongoing business relationship between themselves and users, even if this is exercised through a smart contract or in some cases voting protocols.

“Countries may wish to consider other factors as well, such as whether any party profits from the service or has the ability to set or change parameters to identify the owner/operator of a DeFi arrangement. These are not the only characteristics that may make the owner/operator a VASP, but they are illustrative. Depending on its operation, there may also be additional VASPs that interact with a DeFi arrangement.”

It is now up to national regulators to determine what constitutes “sufficient influence” to determine the scope of current AML/CFT regulations to the DeFi ecosystem. CMG’s transaction monitoring tools can be used to analyze flows of individuals and entities engaging with DeFi protocols. VASPs can prepare for DeFi ML incidents and regulatory announcements by building a robust compliance function using CMG’s tools.

Cryptoassets in focus

What is a Stablecoin?

Definition

Stablecoins are a type of cryptoasset.

As the name suggests, they are designed to maintain a stable price compared to unbacked cryptoassets such as Bitcoin.

Stablecoins are pegged against an asset or assets to minimize their volatility. They are often tied to the US dollar.

Nonetheless, there are few requirements regarding the transparency of the assets backing stablecoins.

For example, Tether, the issuer of the USDT stablecoin, was ordered to pay $41 million by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) as it made “untrue or misleading statements and omissions of material fact in connection with the US dollar tether token (USDT) stablecoin”.

What is a CBDC?

Introduction

Central banks are increasingly interested in using blockchain technology to benefit their payment systems. Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are different from most cryptoassets as they are centralized, stable in value and backed by a central bank. In October 2021, Nigeria was one of the first economies to release its CBDC: the eNaira.

Readers should be especially attentive to the design of the currency studied, as CBDCs can take different forms. Retail CBDCs are a digital version of cash targeted at all economic agents. Wholesale versions are electronic central bank reserves to be used between financial intermediaries. Regardless of the approach taken by governments, CBDCs will remain exposed to exploitation by illicit actors. Nonetheless, their digital nature will make it easier for public and private actors to track and prevent financial crime.

Benefits of CBDCs

As highlighted in the World Economic Forum 2021 Compendium Report on CBDCs and stablecoins, the former can help support the following policy objectives:

- Mitigating currency substitution risk

- Payment system safety and resilience

- Financial inclusion

- Domestic or cross-border payment efficiency

- Monetary policy implementation

- Payment and banking system competitiveness

- Continued access to central bank money for the general public

- Household fiscal transfers

CBDCs and Compliance

Compliance requirements for financial institutions dealing with CBDCs will largely depend on the design chosen by central banks. A first approach would be a two-tiered system in which banks onboard customers and provide a variety of services – including custody – relating to the CBDC. For example, this is the architecture selected by the Central Bank of Nigeria for its e-Naira as detailed in the design whitepaper. A second approach would be to establish a single-tier CBDC with a direct relationship between end-users and the central bank.

Governments which choose a two-tiered system are likely to delegate KYC and AML/CFT requirements to banks. This will resemble onboarding for traditional bank accounts. Nonetheless, these institutions will need to change the way they conduct transaction monitoring – depending on the technology underlying the CBDC. In most cases, this may mean using blockchain analytics tools such as CMG’s tools to detect and prevent financial crime.

Central banks will be responsible for setting standards regarding cryptographic standards and validation methods. AML/CFT requirements will apply to this version of the fiat currency. However, the interoperability features between foreign CBDCs will have an impact on sanctions enforcement.

What is an NFT?

“NFT” stands for “non-fungible token” and they are non-fungible blockchain based assets which can have specific properties.

Fungibility vs Non-Fungibility

To understand the difference between a fungible and non-fungible asset, consider a pile of £1 coins and a pile of Pokemon cards.

If you were asked to give someone £18, then you would select any 18 coins from the pile – confident in the knowledge that they each have the same value.

However, consider a scenario where someone asks you to provide them with £18 worth of Pokemon cards.

To do this, you’d need to understand the value of each card.

After all, the price difference between a common Eevee and a 1999 First Edition Shadowless Holographic Charizard is around £160,000!

The £1 coins are fungible – they are all interchangeable for the same amount, whereas the Pokemon cards are non-fungible.

Non-fungible Tokens

Just like Pokemon cards, but existing on a blockchain, non-fungible tokens have different properties which derive their value. They are therefore a distinct asset class from fungible cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin (BTC) and Ethereum (ETH), which are individually mutually interchangeable – e.g this Bitcoin is worth exactly the same as that Bitcoin.

They exist on blockchains, with the most popular network to launch an NFT being the Ethereum protocol. Though there are also a number of other well known networks which support NFTs, such as Tron, EOS, NEO, Near Protocol, and Flow.

To understand the mechanics of an NFT, we are going to explore how they work under the hood on the Ethereum protocol.

Ethereum Contract Standards

The Ethereum blockchain has the native asset ETH, and it’s also possible to create other assets which can be transferred over the network. To create one of these, you must first decide what properties and functionalities you require and then choose an appropriate framework to build under.

Until recently, the contract standard of choice was ERC20, and this allowed for the creation of a fungible token with limited functionality. This suited many of the projects in the crypto-ecosystem, which wanted their own token without the overhead of creating and maintaining their own blockchain. Due to the ease of creating an ERC20, the vast majority of tokens touted in the 2017/2018 ICO boom were of this variety. The number of ERC20 assets built on the Ethereum network can be seen here. Yet the limited functionality and customization of ERC20s paired with continued innovation in the space meant that new frameworks were required.

Rise of the Non-fungible Contract Standards

While the ERC20 token standard allowed the creation of a digital version of our pound coins, it stopped short at being able to digitalize the Pokemon cards with their myriad of attributes and different values.

However, in early 2018 the ERC721 token standard was launched on the Ethereum network and brought the ability to create non-fungible tokens.

This ability came from the introduction of two critical properties:

Uniqueness

The “tokenMetadata” field can contain a wealth of information about the token and its properties. For our digitalized Pokemon card, it would be information such as the type, HP, image, ability and name. This allows one ERC721 token to be distinct from another ERC721, and therefore hold a different value.

Indivisibility

Unlike an ERC20 token which can be divided up to 18 decimal places – as prescribed in the contract – an ERC721 token is indivisible. As such, the token is either transferred in its entirely or not at all. So just as you cannot move one third of the Mona Lisa without cutting up the painting, you cannot transfer one third of an ERC721 asset.

The first project to make use of these non-fungible properties was CryptoKitties, a digital cat collectable game where a feline’s cattributes – yes you read that right – gave it a value.

These NFTs as well as the name, image and description are stored within the token’s metadata. Whether this information is truly immutable is a debate for another day and depends whether it is stored on or off-chain.

There are now tens of thousands of NFTs which are ERC721 compliant, and many notable projects use this standard. For example:

Yet one challenge with the ERC721 standard is that each ERC721 token – whether digital cat, blockchain-based art or virtual piece of land – must be transferred independently. So, if someone is looking to move their collection of CryptoKitties en mass then they will incur hefty transactions fees. Furthermore, for an application which requires both fungible and non-fungible assets, they are required to create a myriad of different tokens using different contract standards.

The ERC1155 standard was proposed just a few months after ERC721 but is yet to be merged into the Ethereum codebase. It looks to improve upon this with the introduction of a batching ability, support for both fungible and non-fungible assets, and advanced functionality for renting, combining and destroying tokens. This could allow a single contract to create non-fungible Pokemon, with fungible energy and trainer cards, as well as lowering gas costs when batch moving these tokens from one account to another. With the recent increase in awareness and interest of non-fungible tokens, it’s likely we’ll see support and adoption for this token standard grow.

The final contract standard to be aware of with regards to non-fungible tokens is ERC988. This standard allows for the creation of composables – giving your CryptoKitty the ability to own a scratching post, or your Gotchi to wear a wizard hat, or your LAND to have a rollercoaster built on it. It effectively gives the right of an ERC721 – or ERC1155 – to own something, and so if you sell the ERC721 token then the associated ERC998 tokens are sold with it. As with the ERC1155 standard, this is not yet merged into the Ethereum codebase, but many projects are already making use of it to enhance their applications.

So that’s how NFTs work under the hood. They’re primarily ERC721 tokens with unique metadata allowing for distinct valuations and the ability to immutably own and transfer ownership due to being built on top of the Ethereum – or other – protocol.

Regulation

What is AML?

Here, we discuss cryptoasset compliance, blockchain analysis, financial crime, sanctions regulation, and how Elliptic supports our crypto business and financial services customers with solutions.

Anti-money laundering is a top priority for anyone working in crypto, as it helps to increase adoption, encourage safer peer-to-peer lending and safeguard entire communities from illicit trade.

So, what exactly is AML? And how is it helping financial institutions increase their autonomy – even in anonymized environments?

What is AML?

AML is an initialism for anti-money laundering (AML). This approach applies to all financial institutions and activities – but AML is especially necessary when it comes to cryptoassets, as illicit transactions are more commonplace and are harder to detect.

AML might seem like a buzzword to those not working in the finance sector, but it offers true substance and value to financial institutions. AML is a concept implemented through regulation and is underpinned by legislation that offers ways to govern both physical and digital banking and exchange environments.

AML & KYC

As we covered in a previous article, know your customer (KYC) is underpinned by the idea of verifying customers to identify accounts that may be involved in illicit financial activity. Alongside practices such as transaction monitoring and wallet screening, KYC provides a means to detect and prevent money laundering.

It also helps detect bad actors and anomalous behavior before a money trail even begins. Identifying suspicious accounts before their creation means financial environments – especially the much-scrutinized crypto market – can retain customer trust and seek greater stability. And this creates more accessible financial avenues for all of us.

KYC in the context of crypto helps remove accounts associated with money laundering practices from crypto environments and attaches risk profiles to individual customers. It’s the process of employing a sophisticated and rigorous onboarding procedures to gate entry to financial environments.

If there are question marks about an individual yet they qualify to become a customer, they’ll be assigned a risk value and their exchanges will be monitored to make sure they meet cryptoasset exchange compliance.

The Role of AML and AML Legislation

AML plays a vital role in the cryptoasset space. Its pseudo-anonymous – and therefore appealing – nature makes it a marketplace particularly vulnerable to illicit exchanges. AML is needed to ensure digital coins are used only for their intended purpose. We know that criminals are attracted to the crypto market, so AML practices – including all-important KYC processes – are employed to counterbalance this.

Although AML is now a common term, with both customers and providers having a top-level awareness of it, it’s ultimately up to the financial institution to implement it. Depending on the country, state, or region, financial institutions will need to follow AML law, such as:

- The Bank Secrecy Act in the US.

- The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (POCA) and the Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing and Transfer of Funds 2017 in the UK.

- The 5th AMLD in the EU.

AML legislation works to provide definitive guidance for financial institutions and offer instructions that are regularly revised in line with changes to the external environment. As we learn more about cryptoasset fraud, we can use this intelligence to create more robust strategies to detect and prevent financial crime.

Progressing AML Practices Through Criminal Intelligence

So, where better to look for an understanding of AML than within the most common routes of criminal activity?

AML typologies tell us more about the approach of bad actors in the crypto market and how they’re most likely to utilize digital environments to enable money laundering, either through illicit activity on the platform or by using a crypto-to-fiat exchange as an off-ramp for more complex money laundering paths.

What is KYC?

KYC verification is required by many major cryptoasset exchanges worldwide before their services can be utilized. The verification intends to make it safer for crypto users and companies operating in the space.

What is KYC?

KYC stands for “Know your customer”. Many financial institutions employ the process – including cryptoasset exchanges – to verify a potential customer’s identity.

Several methods can establish identity verification. These most commonly involve the provision of some form of identification like a passport, ID card or a driving license. In some cases, video evidence and voice recognition can be required to complete KYC.

The process is in place primarily to obtain information and understand the potential risks that customers may present. KYC verification ensures that criminal entities who commit financial crimes – such as money laundering – can’t use anonymity to misuse the services without consequence. As a result, this a risk management process that keeps the platform and its users safe.

Aside from being a crucial element of risk management, KYC is a regulatory requirement enforced globally through various rules and regulations. Failure to comply with KYC rules and regulations will mean restricted or blocked access to platforms, or locking specific features to prevent misuse.

KYC compliance is essential for the cryptoasset industry and the companies operating within it to be considered part of a reputable financial system. Exchanges and other crypto companies without KYC verification are an immediate red flag, as are users who transfer funds to or from these sources.

KYC Compliance Requirements

There are three critical steps to a KYC compliance framework: customer identification, customer due diligence and enhanced due diligence.

Customer Identification

This process involves stringent checks on a customer’s documentation to verify their identity. The information must be scrutinized to ensure the person in question isn’t included on any sanctions lists – such as the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). Identifying beneficial ownership is required if a customer is a legal person rather than a natural one.

Customer Due Diligence (CDD)

You must apply due diligence to collect all required data from trusted sources on your customer. The type of due diligence applied should be based on various factors – including geography, customer type, industry type, reputational risk, political exposure, product and usage.

Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD)

If a customer is deemed to have a higher risk – which is calculated as a risk score based on an amalgamation of risk factors – it requires EDD. For example, this might be customers with political exposure or a country of origin considered “high risk”. EDD measures mean that you have to monitor the customer more intensely and conduct deeper investigative research.

Once you establish the identity, ongoing monitoring is required alongside an actively maintained risk profile that meets regulatory requirements. You should enforce customer exits if customers exceed risk tolerance levels at any point or if they fail to provide the required information.

Why Is KYC so Important in Crypto?

Crypto is pseudo-anonymous by nature, which means many in the crypto community use an assumed name (pseudonym) to shield their real identity. This could be for many reasons – such as personal privacy or security. However, without KYC verification, this pseudo-anonymity can also lead to illicit activities by prohibited persons.

Cryptoassets have historically been used to facilitate a number of illegal activities such as money laundering, financing terrorism and tax evasion. Sensationalized stories have interrupted the industry and prevented more mainstream adoption of legitimate crypto projects. It’s for these reasons that KYC, among other processes, are important to help change the narrative around the crypto industry.

KYC allows third-party intermediaries – such as crypto exchanges – to understand users’ identities, while simultaneously enabling them to maintain the benefits of pseudo-anonymity on the blockchain. KYC offers the crypto ecosystem more robust safety – promoting trust for increased retail and institutional investors.

KYC’s Relationship With Cryptoasset Exchanges

KYC regulatory requirements for cryptoasset exchanges can vary between territories.

For example, FinCEN requires US-regulated crypto exchanges to carry out KYC during customer onboarding, alongside the implementation of stringent AML measures. However, currently in the EU, exchanges that deal solely in crypto-to-crypto transactions may sit in a regulatory grey area. In contrast, exchanges that transact in fiat-to-crypto must carry out KYC and AML compliance programs.

Decentralized exchanges that currently operate without any third-party intervention may allow users to use peer-to-peer transactions without KYC or AML protocols. However, these exchanges are under growing pressure to adopt regulatory compliance and are slowly coming to terms with this and its benefits for their customers.

While many within the crypto industry understand the value of KYC compliance programs, some remain skeptical. With time, the narrative changes as these people realize the benefits of a KYC compliance ecosystem that offers increased trust, confidence in non-criminal counterparties, and a reduced risk of fraud.

KYC vs. Anonymity & Decentralization

As previously mentioned, some people in the crypto industry feel KYC protocols are an infringement on their privacy. However, anonymity has historically allowed crypto service providers to be exploited for financial crime and has facilitated the spreading of illicitly-gained funds.

Appropriate KYC compliance programs reduce the risks posed by criminal entities who might seek to use an exchange for any number of illegal purposes. Those in the crypto industry who want to see it grow should highly regard limiting the spread of illicit funds and the risk of fraud.

Anonymity is maintained, so only the virtual asset provider (VASP) and the government hold the provided information. This is known as pseudo-anonymity. There’s no regulatory requirement to disclose any information publicly, and law-abiding crypto users have no reason to fear intervention from third parties.

Decentralized finance differs from the traditional financial system. In the latter, control is transferred from a centralized authority to a network – such as a bank or government entity. Decentralized networks allow crypto users to transact directly without a third-party intervening.

Some people in the industry feel KYC is an affront to the guiding principles of decentralization on which crypto is built. But even with KYC protocols in place, crypto users can still transact directly with no need to pass funds through a third-party intermediary.

Decentralization doesn’t preclude KYC requirements. Under the newly promulgated Financial Action Task Force (FATF) standards, it has been proposed that even the most highly decentralized organizations are likely to have some persons or entities that maintain a level of control that can be brought into scope for KYC-related regulatory oversight.

KYC and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CFT)

Crypto has historically been attractive to terrorists due to its non-intermediated and anonymous (or pseudo-anonymous) nature. These characteristics enable them to move and launder illicitly gained funds, which they subsequently use to finance terrorist activities.

Cryptoassets such as privacy coins can better mask the owner’s identity and the volume of transactions. They can also attract bad actors such as terrorist organizations. Privacy coins can obfuscate information to the degree that an individual may not be linked to a transaction. However, a centralized, KYC-compliant exchange will likely eventually be required to convert crypto funds into fiat currency.

Alongside AML, a key objective of KYC compliance is to prevent terrorists from using crypto exchanges to move funds anonymously. Non-KYC compliant exchanges would present a significant risk of facilitating terrorist financing globally.

What is Travel Rule?

The Travel Rule requires financial institutions to disseminate information to the receiving financial institution of payments above a certain threshold.

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) – part of the United States Department of the Treasury – describes the Travel Rule as “preserving an information trail about persons sending and receiving funds through funds transfer systems”. This information then helps “law enforcement agencies detect, investigate and prosecute money laundering and other financial crimes”.

FinCEN – the primary regulator for most US financial institutions – is the enforcing agency of Travel Rule compliance. The Travel Rule is a component of the Bank Secrecy Act, which requires financial institutions to work with law enforcement agencies to combat money laundering and illicit activity. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) – an inter-governmental body with a similar directive – has also provided Travel Rule recommendations to its 39 member countries.

Who is Obligated to Follow the Travel Rule?

FinCEN’s Travel Rule applies to most financial institutions for transactions above a $3,000 threshold. In 2020, the FinCEN issued an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking to lower the Travel Rule threshold from $3,000 to $250, though this proposal has not yet gone into effect. For comparison, the FATF recommends a minimum of $1,000 for the Travel Rule to apply.

In this context, financial institutions are defined as “banks; securities brokers or dealers; casinos subject to the Bank Secrecy Act; money transmitters, check cashers, currency exchangers, and money order issuers and sellers subject to the Bank Secrecy Act.” This definition also applies to virtual asset service providers (VASPs).

There are select exceptions to Travel Rule obligations – including point of sale transactions, bank direct deposits and electronic fund transfers defined by the Electronic Fund Transfers Act (Regulation E.) Currently, Regulation E does not exempt cryptoassets, though this exclusion is frequently debated.

What Information is Needed For Travel Rule Compliance?

For financial institutions sending the money transfer, they must document and send the following information to the receiving financial institution:

- the name of the transmittor;

- the account number of the transmittor, if used;

- the address of the transmittor;

- the identity of the transmittor’s financial institution;

- the amount of the transmittal order;

- the execution date of the transmittal order; and

- the identity of the recipient’s financial institution.

For financial institutions receiving the money transfer, they must document the following:

- the name of the recipient;

- the address of the recipient;

- the account number of the recipient; and

- any other specific identifier of the recipient.

This information must be maintained for five years by both parties in compliance with the Travel Rule. Financial institutions have no obligation to share this information with the government unless a Suspicious Activity Report is filed.

The Travel Rule and VASPs

Travel Rule compliance is relatively straightforward for most financial institutions as this information is likely already available for each customer. It is slightly more complex for VASPs or businesses engaging in crypto transactions as customers’ identities are often obfuscated.

Banks use the SWIFT network – a global banking telecommunications system – to deliver necessary Travel Rule information to one another. For VASPs, there is no equivalent to the SWIFT network for securely sending data between parties. VASPs face the additional challenge of identifying both the originator and the beneficiary of a transaction, information that might not be readily available.

Elliptic’s Discovery tool holds detailed information on more than 1000 VASPs worldwide, profiling their regulatory compliance, AML/KYC programs, areas of operation, and blockchain activity. This information will help screen and benchmark VASPs before directly engaging with them.

Cryptocurrency

Intelligence

At CMG, Cryptocurrency Intelligence lies at the heart of our mission to protect the digital economy. It’s a comprehensive process that involves collecting, analyzing, and interpreting blockchain data to identify patterns, trace transactions, and uncover hidden connections within the cryptocurrency ecosystem.

Our system integrates both on-chain (blockchain-native) and off-chain (external) data sources to create a full picture of digital asset activity. This includes transaction histories, wallet behaviors, counterparty identities, and jurisdictional data. By combining these layers, we can detect anomalies, flag suspicious transactions, and track the movement of funds in real time.

We apply Cryptocurrency Intelligence to:

Monitor and analyze transactions across thousands of Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASPs).

Assess risk exposure by identifying high-risk wallets, addresses, and counterparties.

Support compliance teams in meeting AML and regulatory obligations.

Assist investigations in tracing funds related to fraud, scams, or criminal enterprises.

Our proprietary algorithms and risk models are specifically designed to uncover hidden patterns that might indicate money laundering, fraud schemes, or other financial crimes. We enrich these findings with jurisdictional insights, KYC data partnerships, and real-time alerts — making our intelligence system not just a tool, but a strategic asset for businesses navigating the complex world of crypto.

At CMG, Cryptocurrency Intelligence empowers our clients to stay ahead of threats, operate with confidence, and build a safer, more transparent digital economy.

Our Journey: Rising from the Ashed if Crypto Failures

The Crypto collapse that shook the industry

The crypto market has seen its share of turbulence, with some of the biggest names crumbling under the weight of mismanagement and market volatility. In 2022, the collapse of FTX sent shockwaves through the industry, leaving millions of users stranded as the exchange filed for bankruptcy after a liquidity crisis exposed billions in missing funds. Similarly, Celsius Network, once a popular lending platform, halted withdrawals in June 2022, citing “extreme market conditions,” before filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, with over $4.7 billion in liabilities. Voyager Digital, another crypto lender, followed suit, declaring bankruptcy shortly after, unable to recover from a $650 million loan default by Three Arrows Capital, a hedge fund that itself imploded. These failures weren’t just financial—they shattered trust, leaving clients desperate for a safe haven to protect their remaining assets. Many of these users, from individual investors to small businesses, found themselves holding non-valued assets like frozen accounts or devalued tokens, unsure of where to turn. The fallout was a stark reminder of the risks in an unregulated space, but it also created an opportunity for stable, trustworthy platforms to step in. For us, this was a defining moment to prove our commitment to the crypto community.

Welcoming Clients and Assets with Open Arms

As these companies crumbled, we saw an influx of clients seeking refuge, bringing with them their stories, their frustrations, and their non-valued assets. Many of FTX’s former users, for instance, had been locked out of their accounts for months, holding tokens that had plummeted in value or were tied up in bankruptcy proceedings. Celsius clients faced similar woes, with some losing access to life savings they had invested in what they thought was a secure platform. We opened our doors to these individuals, offering a seamless onboarding process to help them regain control of their financial futures. Our team worked tirelessly to assess and integrate their non-valued assets—whether it was converting devalued tokens into more stable holdings or providing guidance on navigating the volatile market. We also prioritized transparency, ensuring every client understood our security measures, from cold storage solutions to regular audits, which stood in stark contrast to the opaque practices of the failed companies. By focusing on education and support, we turned a crisis into an opportunity to build lasting relationships. Over time, these clients became some of our most loyal advocates, sharing how our platform gave them a fresh start in the crypto world.

Building a Stronger Future Together

The influx of clients and assets from these bankruptcies wasn’t just a chance to grow—it was a responsibility to uphold the trust placed in us. We saw firsthand how the failures of companies like Voyager and Celsius left users feeling betrayed, with many losing faith in crypto altogether. Our mission became clear: to not only provide a safe platform but to educate and empower our users to thrive in this space. We expanded our Learn resources, offering guides on risk management, asset diversification, and spotting red flags in crypto platforms, directly addressing the lessons from these collapses. For the non-valued assets that came our way, we developed strategies to help clients recover value where possible, whether through staking opportunities or gradual reinvestment in more stable coins. We also strengthened our infrastructure, implementing advanced security protocols to ensure history wouldn’t repeat itself on our watch. Today, we’re proud to say that many of those who joined us during this turbulent period have not only recovered but have grown their portfolios with us. This journey has solidified our role as a beacon of stability in the crypto world, and we’re committed to continuing this legacy for every user who joins our community.

Glossary

A

Address: A cryptoasset address is a unique identifier that serves as a virtual location where a cryptoasset can be sent. The address can be freely shared with others to facilitate transactions.

Alphanumeric: Alphanumeric data contains both numbers and letters. A Bitcoin address is an example of alphanumeric data.

Altcoin: The term “altcoin” typically refers to any cryptocurrencies other than Bitcoin.

Anonymity: This is the condition of being anonymous, so your identity and/or actions are not publicly known.

Anti-Money Laundering (AML): Criminals use money laundering to conceal their crimes and the money derived from them. Anti-money laundering (AML) seeks to deter criminals by making it harder for them to hide ill-gotten money. AML regulations require financial institutions to monitor customers’ transactions and report on suspicious financial activity. In jurisdictions that regulate cryptocurrency service providers, the AML and compliance standards for traditional finance often apply to cryptocurrency too.

B

Bank Secrecy Act (BSA): The Bank Secrecy Act of 1970 (BSA) – also known as the Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act – is a US law requiring financial institutions in the United States to assist government agencies in detecting and preventing money laundering. Specifically, the act requires financial institutions to keep records of cash purchases of negotiable instruments, file reports if the daily aggregate exceeds $10,000, and report suspicious activity that may signify money laundering, tax evasion or other criminal activities. In October 2019, FinCEN issued a joint statement with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) to provide a united anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) front and explain how they define and regulate cryptoassets. The three leading US financial regulators remind persons engaged in activities involving cryptoassets of their AML/CFT duties and that they should make sure that they stay compliant with the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA).

Binance Chain: Binance Chain is a protocol launched by the crypto exchange Binance. It has the native cryptocurrency BNB, however this was first released on the Ethereum blockchain and has since been token swapped. This function-rich blockchain allows users to create their own tokens on it, utilize an integrated decentralized exchange and use the Binance Smart Chain, which is a parallel blockchain allowing smart contract functionality.

Bitcoin: Bitcoin (BTC) is a peer-to-peer (P2P) version of electronic cash that allows online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution. All Bitcoin transactions are visible on a public ledger called a blockchain which anyone can download a copy of in order to verify and process transactions. The total supply is limited to just under 21 million and a full bitcoin can be divided up to 8 decimal places, the smallest of which is called a ‘satoshi’ after the anonymous creator of the network, Satoshi Nakamoto.

Bitcoin ATM: A Bitcoin ATM (Automated Teller Machine) is a kiosk that allows a person to purchase Bitcoin by using cash or debit card. Some Bitcoin ATMs offer bi-directional functionality enabling both the purchase of Bitcoin as well as the sale of Bitcoin for cash. Bitcoin ATMs do not connect to a bank account and instead connect the user directly to a Bitcoin wallet or cryptocurrency exchange.

Blockchain: A blockchain is the transaction database shared by all nodes participating in a specific cryptoasset network. A full copy of a network’s blockchain contains every transaction ever executed in the asset. It was first introduced in the Bitcoin whitepaper published in October 2008 as the underlying protocol to allow truly peer-to-peer transactions.

Blockchain Analysis/Blockchain Analytics: Blockchain analysis combines transaction information from the blockchain with other data in order to gain insights into the flow of cryptoassets between actors. This information can be used to identify financial crime and meet regulatory requirements.

Blocks: Each block in the blockchain is a collection of transactions that is linked to the previous block in the chain by means of a cryptographic hash to ensure it is valid and a legitimate connection to the previous block. After a block is added to the blockchain, the mining process to build and validate the next block begins.

BNB: BNB – or Binance Coin – started out as a utility token available on the Binance exchange. Unlike mainstream cryptocurrencies, it is meant to be used within the eponymous ecosystem.

C

Cold Storage: When cryptocurrency is referred to as being held in cold storage it means the associated private key for the address is being held offline. The most common forms of this are a hardware wallet or written down physically – such as on a piece of paper.

Crypto Custodian: A Crypto custodian stores digital assets on behalf of retail and institutional customers. Often, a crypto exchange also performs this role.

Cryptoasset: A cryptoasset is a digital asset that is secured with cryptography and where transactions are distributed and validated by a decentralized set of participants, and recorded on a public ledger known as a blockchain.

Cryptocurrency: The term “cryptocurrency” can be used as an umbrella term for virtual forms of money, but is generally used when talking about assets which are supported by a blockchain like Bitcoin and Ethereum. Cryptocurrencies are not issued or controlled by any government or other central authority. They exist on peer-to-peer networks of computers running free, open-source software. Generally, anyone who wants to participate by owning, sending or spending can do so. The abbreviation “crypto” is often used when speaking and writing.

Cryptocurrency Exchange: A cryptocurrency exchange is a business allowing customers to buy or sell digital assets using either fiat or cryptocurrencies. Examples include Coinbase and Kraken.

Cryptography: Cryptography is the use of mathematics – specifically encryption – to secure computer networks and digital data, which ensures information or systems can only be accessed by the intended recipient.

D

Dark Web: The dark web is a subset of the deep web, which is a part of the internet that isn’t indexed by search engines such as Google. It requires the use of anonymizing browsers like Tor to access. Most dark web marketplaces conduct transactions in Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies. The inherent anonymity of the dark web attracts scammers and criminals, but not everything there is nefarious or illegal. The Tor network began as an anonymous communications channel, and it still serves a valuable purpose in helping people communicate in environments that are hostile to free speech.

Decentralized Application (dApp): Decentralized Applications (dApps) are a computer application that runs on a decentralized computing system such as Ethereum.

Decentralized Autonomous Organisation (DAO): A Decentralized Autonomous Organisation (DAO) is a computer program with no manager or leader running on a peer-to-peer network with a series of smart contracts encoded into the blockchain. Hence, there is no need for any human intervention, as the DAO runs completely autonomously on the blockchain. The intention of a DAO is that it is an organisation which can run with decentralized governance. DAOs have been formed to try to collectively buy a copy of the US constitution, to be creator-led communities, and work as investment firms.

Decentralized Exchange (DEX): A Decentralized Exchange (DEX) is a combination of smart contracts which enables users to swap cryptoassets peer-to-peer, without the need for a trusted intermediary. This differs from a traditional centralized exchange where there is an off-chain order book and users must deposit cryptoassets into the custody of the exchange in order to transact.

Decryption: Decryption is the process of decoding information and the opposite process from encryption. It converts the cipher text back into plain text to reveal the original message.

Decentralized Finance (DeFi): Decentralized finance (DeFi) is a peer-to-peer, decentralized, censorship-resistant financial system. Common DeFi applications include crypto wallets, lending, borrowing, spot trading, margin trading, interest-earning, market-making, derivatives, options and more.

Digital Signature: A digital signature is a mathematical scheme for verifying the authenticity of digital messages or documents. A valid digital signature – where the prerequisites are satisfied – gives a recipient very strong reason to believe that the message was created by a known sender (authentication), and that the message was not altered in transit (integrity).

Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT): Distributed Ledger Technology – also known as shared ledger or DLT – refers to peer-to-peer networks which reach consensus to ensure that the replication across nodes is undertaken. Unlike distributed databases or centralized services, there is no central administrator and participants and nodes can be across multiple sites, countries or institutions. The most well known example of Distributed Ledger Technology is a blockchain.

E

Encryption: Encryption is the process of encoding information. This process converts the original representation of the information – known as plaintext – into an alternative form known as ciphertext. The opposite process is decryption.

Ethereum: The Ethereum blockchain is a network with the ambition of being a decentralized world computer. As such, it offers a more function rich protocol than the Bitcoin blockchain and allows users to transfer the native asset Ether (ETH) as well as creating smart contracts and tokens, or creating more complex decentralized applications (dApps). Ethereum was launched in 2015 and it’s co-creator Vitalik Buterin is a well known individual in the blockchain world – often speaking at conferences and being active in the space.

F

FATF Travel Rule: The FATF Travel rule states that virtual asset providers (VASPs) must identify the senders (originators) and receivers (beneficiaries) of cryptocurrency transactions initiated by their users once it goes above a certain amount, which varies by country or jurisdiction. Authorities can take freezing action and prohibit the conducting of transactions which are the subject of UN Security Council resolutions relating to the prevention and suppression of terrorism and terrorist financing.

Fiat Currency: A fiat currency is a national currency – often established as legal tender by government regulation – that is not pegged to the price of a commodity such as gold or silver.

FinCEN: The Financial Crimes Network (FinCEN) is a bureau of the United States Department of the Treasury. It is tasked with safeguarding the financial system from illicit use, combating money laundering and promoting national security through the collection, analysis and dissemination of financial intelligence and strategic use of financial authorities.

Fork: A fork in a blockchain represents a split where two competing chains are formed from the same history. It can happen unintentionally – where two miners find a successful block at the same time, for instance. Alternatively, a fork can be initiated by developers for a number of reasons, like offering more functionality or helping to resolve a major hack. Examples include Bitcoin in 2017, which led to the creation of Bitcoin Cash, and Ethereum in 2021, known as the London fork, which served to help reduce transaction fee volatility.

FUD: FUD is an acronym often encountered in the crypto world and stands for “fear, uncertainty and doubt”. The term is often encountered on social media and can lead to a cryptocurrency price drop.

Fungible Token: A token which is fungible means that any unit of the asset is interchangeable with any other. This is the same property which coins in a purse have – a $1 coin has the same value as any other $1 coin. The opposite of this is non-fungible tokens.

G

Genesis Block: The genesis block is the term used to refer to the first block created on a blockchain. It therefore has height 0 and contains the first transactions ever processed on the network.

H

Hacking: Hacking is an attempt to gain unauthorized access to a computer system or network.

Halving: The initial block reward for a Bitcoin block being mined was 50 BTC. This amount halves after every 210,000 blocks so that, on current forecasts, it is estimated that there will be no further BTC created in or near the year 2140, as by then the halving process will have exceeded the eight decimal places by which a bitcoin can be subdivided. As such, there will only ever be a little under 21 million BTC created. Halving refers to the process. The current halving rate and countdown can be viewed here.

Hardware Wallet: A hardware wallet is physical device for storing a user’s private key, which in turn is used to facilitate cryptocurrency transactions.

Hash Rate: A hash rate is a measure of the combined computational power at any one time that is being used to mine and process cryptoasset transactions.

HODL: HODL is a term in the industry for holding onto your crypto and not selling it – even in a turbulent market. The term is sometimes misattributed to be an acronym for “hold on for dear life”, but it is actually from a Bitcointalk forum post in 2013 where a user misspelled the word “hold”.

Hyperledger: A hyperledger is a global enterprise blockchain project created in December 2015 by the Linux Foundation. Participants include Samsung, IBM and Microsoft. It works by providing the necessary infrastructure and standards, guidelines and tools to build open source blockchains and related applications for use across various industries.

I

Initial Coin Offering (ICO): An initial coin offering (ICO) is a digital way to raise funds within a limited period of time by issuing a cryptocurrency that is related to a specific project, business model or idea. The cryptocurrency typically is created and disseminated using distributed ledger or blockchain technology and may be tradable on specific platforms. Between 2017 and 2018 there was a boom of ICOs, with the majority being run on the Ethereum blockchain.

J

K

Know-Your-Customer (KYC): Know-your-customer (KYC) standards help protect the financial services industry against fraud, money laundering, corruption and terrorist financing. They involve the checking and verifying of a client’s identity both at the onboarding stage and as part of continuing obligations.

L

Litecoin (LTC): Litecoin is one of the more successful alternative cryptocurrencies to Bitcoin. The former shares a number of characteristics with Bitcoin – including the codebase – but it has a far greater distribution potential of 84 million coins.

M

Mainnet: Mainnet is a term used to describe individual and independent blockchains running their own protocol and utilizing their own technology. Examples include EOS, Polygon and VeChain.

Mining: Mining is the process by which transactions are added to the blockchain. An associated function of mining is it is responsible for introducing new coins into the existing circulating supply as rewards for the individuals responsible for verifying the earlier transaction. There are a number of mining methods blockchains can use such as proof of work and proof of stake.

Mixer: A mixer is a service where a user pools together some of their cryptoassets with other users’ funds and then receives some funds back from this pool. The aim is to make it difficult or impossible to trace the original source of the funds since all the funds are mixed together. Mixers are commonly used by those seeking financial privacy, or by criminals seeking to launder proceeds of crime.

Mixer First Funding: Mixer first funding refers to addresses that receive their first transaction from a mixer, coin swap service or a low know-your-customer (KYC) exchange.

N

Native Asset: A native asset – or sometimes seen as native cryptocurrency – is simply the cryptocurrency that is issued directly by the blockchain protocol on which it runs. Hence, for example, ETH is the native asset of Ethereum.

Neobank: A neobank is an institution that provides banking services exclusively online via apps and online platforms.

Node: Any computer that connects to a particular network is called a node. Nodes that fully verify all of the consensus rules are called full nodes.

Non-fungible Token: A non-fungible token (NFT) is a kind of crypto asset that records ownership of a digital item and unlike cryptoassets such as Ether (ETH) and Bitcoin (BTC), is not mutually interchangeable. Each NFT is a unique asset in the digital world and can be bought and sold like any other item.

NPRM: A notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) is a public notice that is issued by law when an independent agency of the US government wishes to add, remove or change a rule or regulation as part of the rulemaking process.

O

P

Paper Wallet: A paper wallet is an offline method for storing your public and private keys. There are different websites and apps available to help cryptocurrency owners download their keys into a secure printed paper format. However, it could be as simple as a slip of paper with the private key details written on it.

Peer-to-Peer (P2P): Peer-to-peer describes the decentralized nature of the computer network that underpins much of the crypto industry. It provides for the ability of each computer in a network to act as a server and hence remove the need for a central server.

Privacy Coin: A privacy coin is a type of cryptoasset based on a blockchain that does not publicly reveal all details of transactions – making blockchain analytics difficult or impossible. Examples include Monero and ZCash.

Privacy Wallet: A privacy wallet is essentially wallet software that provides additional privacy enhancing functionality.

Private Key: Every address has an associated private key which must be kept secret, since knowledge of it allows the owner to send or spend any cryptocurrency associated with the address. It can be thought of as the password which allows someone to access their emails. A private key is created through a mathematical process and is a string of numbers and letters. As such it can be kept online – referred to as hot storage – or offline, which is known as cold storage. The private key is generated from the public key and this public-private pair of keys is required for anyone transacting cryptocurrencies. It is used when making a transaction to confirm that the appropriate person or entity is behind the transaction.

Protocol: A protocol is the language which participants in a network must speak if they wish to take part. The Bitcoin Protocol is a communications specification. The protocol is defined by the rules for network communication, as opposed to the rules for transaction or block validity (consensus rules). There is currently no formal written standard for the Bitcoin Protocol; instead, there is a reference client, which is considered to be the correct specification of the protocol. The same protocol could theoretically be used by multiple networks, but in practice this is rare for public networks, usually only happening when there is a hard fork. In many cases, these hard forks will also be accompanied by a planned protocol change.

Pseudonymous: The nature of blockchain transactions, verified with a public key and the details stored on the blockchain, means that most blockchain transactions are not anonymous but pseudonymous, in that details of public addresses and transfer of data to and from those addresses is readily available.

Public Key: A public and private key pair are created using a mathematical process, and then using a series of hash functions the public key is transformed into a more user friendly format referred to as an ‘address’. This is used to send and receive cryptocurrency. Unlike the private key, the public key can be shared publicly without fear of loss of funds; however, sharing this information can be used to connect the public key (and therefore address) to an entity using blockchain analytics.

Pump and Dump: Much like pump and dump scams affecting regular stocks and shares, the process occurs in the crypto space when malevolent individuals or entities spread misinformation about an asset to artificially raise the price, at which point they will off-load their investment.

Q

R

Ripple: Ripple is the company behind another popular eponymous crypto also known as XRP.

S

Sanctions: Sanctions are instruments of foreign policy that are imposed by countries or international organizations on other countries, or on entities and individuals within those nations. They are designed to penalize illegal activities, including financial crimes, humanitarian crimes and terrorism, or to achieve diplomatic objectives, economic sanctions specifically prevent firms and individuals from doing business in, or with, countries named on a sanctions list.

Satoshi Nakamoto: Satoshi Nakamoto was the author of the original paper proposing a peer-to-peer electronic cash system which introduced the world to Bitcoin. Whilst Nakamoto’s identity has remained elusive, the Satoshi is officially recognized as the smallest unit of a Bitcoin – being equivalent to a single 100 millionth.

Security Token: A security token represents a stake in an asset, most often a company, but in a digitized form Most traditional securities like shares, bonds and ETFs can be digitized – or tokenized – to become a security token. While they use the underlying blockchain technology, these assets are different to cryptocurrencies.

Silk Road: Silk Road was the first modern darknet market. This online black market operated on the dark web, which was accessed through software allowing anonymous communication – such as Tor. Users could access the network and purchase a host of illegal items and services using cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. Silk Road was shut down in 2013, but a number of similar services have emerged since then.

Smart Contract: A smart contract is a computer program or a transaction protocol which is intended to automatically execute, control or document legally relevant events and actions according to the terms of a contract or an agreement. It was initially concepted by Nick Szabo in 1998 and later implemented on blockchains such as Ethereum.

Standard: A standard is a formalized written specification of a set of rules. If something adheres to the rules, it can be said to be standard-compliant, which may confer certain benefits. Examples include the ERC20 standard for fungible tokens in Ethereum, and the RFC821 standard for email over the internet using SMTP. A standard is often the formal definition of the rules which define a protocol – such as in the case of SMTP and RFC821.

T

Token: The term token refers to a programmable unit of value which is recorded and transferred on a blockchain. However, it is distinct from the native asset which is the cryptocurrency created by the protocol and used to pay fees, created as a block subsidy or used in the consensus protocol. The most popular token standard is ERC-20 on the Ethereum blockchain. Tether (USDT) is an example of a token on the Ethereum blockchain. Ether (ETH) is the native asset of Ethereum.

Token Swap: A token swap is when a blockchain migrates from having their token living on another blockchain, for example Ethereum, to their own blockchain. This mainly occurs when a project uses a pre-existing blockchain to develop and grow their community, and then once their own mainnet is ready, they launch a native asset on this. Users can then swap their tokens on the other blockchain for native assets on the mainnet.

Tokenize: To tokenize an asset is to convert the ownership rights into a digital token for the purposes of incorporating the asset onto a blockchain or other distributed ledger.

Transaction Fee: The transaction fee is applied to any transaction, for example when converting fiat currencies into crypto currencies or one cryptocurrency to another. charge is determined by network capacity to entice the miner of the blockchain to include the transaction in an upcoming block – thereby processing the transaction. The principal of the transaction fee, however, is exactly the same principal of any other traditional transaction fee such as converting sterling into dollars or vice versa.

U

Unbanked: Unbanked is a term used to describe those individuals who are either unable to or have chosen not to use traditional banks or similar entities for their financial transactions. Hence they could be reliant on cryptocurrencies and distributed ledgers for any transaction that does not involve literally handing over fiat currencies.

Unregulated: Simply any aspect of crypto or indeed regular financial services transactions that is outside of an existing regulatory regime.

Utility Token: A utility token is a blockchain-based asset bought with the intention to be used for a specific product, service or application in the future. They are not used with the intention of providing a return but, as the name suggests, the tokens are to be utilized in some form. Hence they will have some inherent functionality. An example is Binance Coin.

V

Vanity Address: A vanity address is one in which a number of the alphanumeric characters in an address has been adapted to include a specific word or phrase. Often many millions of combinations may need to be generated before the specific phrase or word is generated, but the outcome will be an address which is personal and easily identifiable but which retains its security.

Virtual Asset Service Provider: The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) describes a virtual asset service provider (VASP) as an entity that facilitates any of these five business activities; the exchange between virtual assets and fiat currencies; the exchange between one or more forms of virtual assets; the transfer of virtual assets between crypto wallets; the safekeeping and/or administration of virtual assets or instruments enabling control over virtual assets; or the participation in and provision of financial services related to an issuer’s offer and/or sale of a virtual asset.

W

Wallet: A wallet is a collection of cryptoasset addresses and the corresponding private keys. They allow cryptoassets to be stored, keeping them safe and accessible. They also allow you to send, receive, and spend cryptoassets. Wallets can be self-hosted (where you retain control of the private keys) or hosted (where a custodian stores the private keys on your behalf).

Wei: Wei is the smallest denomination of Ether (ETH), the cryptocurrency used on the Ethereum network. 1 Ether = 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 Wei Wei and other denominations of Ether, such as Gwei – 1 Gwei = 1 million Wei – may be useful for describing small value transactions, typically used for transaction fees or when setting the gas limit of a transaction on Ethereum.

Whales: A whale is an individual or entity that holds significant amounts of any cryptocurrency. Such is the magnitude of their ownership that there is potential to manipulate the valuation of the currency being held.

Whitelist: The term whitelist refers to a list of allowed and identified individuals, institutions, computer programs, or even cryptocurrency addresses. In general, whitelists are related to a particular service, event, or piece of information.

X

XRP: XRP is the ticker symbol for the Ripple cryptocurrency and digital payment network first released in 2012. Ripple’s products are more akin to the services provided by SWIFT, in that they focus on providing a global payments network and currency exchange services.

Y

Z

Chain Monitoring Group

We provide cutting-edge solutions for cryptocurrency incident response, transaction monitoring and compliance.

Real-time Crypto & Stock trading possibilities.

Contact us

Account reletaited Email: account@chain-monitoring.com

Phone: +44 (020) 7007 8976

Adress: 1 Canada Square/ 40 Bank street,

Canary Wharf,

London E14 5NR,

UK

BACKED BY